- HOME

- 【R&D Theory】Why has Toray been able to continue conducting basic research, even with no market, for half a century?

【R&D Theory】Why has Toray been able to continue conducting basic research, even with no market, for half a century?

As science advances and matures, the foundation of manufacturing, research and technological development (R&D), is becoming increasingly sophisticated. How can we continue to create new materials that will bring about essential innovation in these rapidly accelerating times?

In this installment of “Cutting-Edge Materials,” we’ll examine the role of materials manufacturers in creating the building blocks of our lives, ranging from chemistry to biotechnology, with a conversation between Toray Industries’ Executive Vice President and CTO Koichi Abe and Leave a Nest CEO Yukihiro Maru, who has been involved in the creation of numerous innovations in deep tech.

■Why invest in basic research when there is no market for it?

Maru: In 2002, I founded a company called Leave a Nest with some of my fellow science and engineering graduate students.

We started out with a "science experiment class" to show children the fun and excitement of cutting-edge science, and now we’re working to implement science and technology to solve social issues with the support of many researchers and corporate laboratories.

Today's global challenges won’t be solved by a single, magic bullet technology. To solve the difficult, deep issues, we need to combine technologies, transcend the boundaries between countries, universities, companies, ventures, and individuals. I call it “Deep Tech.”

Toray has developed a number of excellent materials over a long period of time. I’m so excited to be able to sit down with Mr. Abe, the CTO of the company.

Abe: The fiscal year before 2002, when you started Leave a Nest, Toray was in the red on a non-consolidated basis for the first time since its establishment. We were all in crisis mode, trying all kinds of management reforms. But even under all that pressure, we established the New Frontiers Research Laboratories in 2003, keeping an eye on the future.

Originally, we were going to call it "Advanced Research Laboratories,” but as you’ve said, we realized that in the future, we won’t create anything new without bringing together technologies and knowledge from different fields. That's why we put the word "frontier" in the name.

Maru: Right at the same time I was starting my company, Toray was also working toward combining technologies. This might be a very simple question, but what has been the focus of Toray's material development?

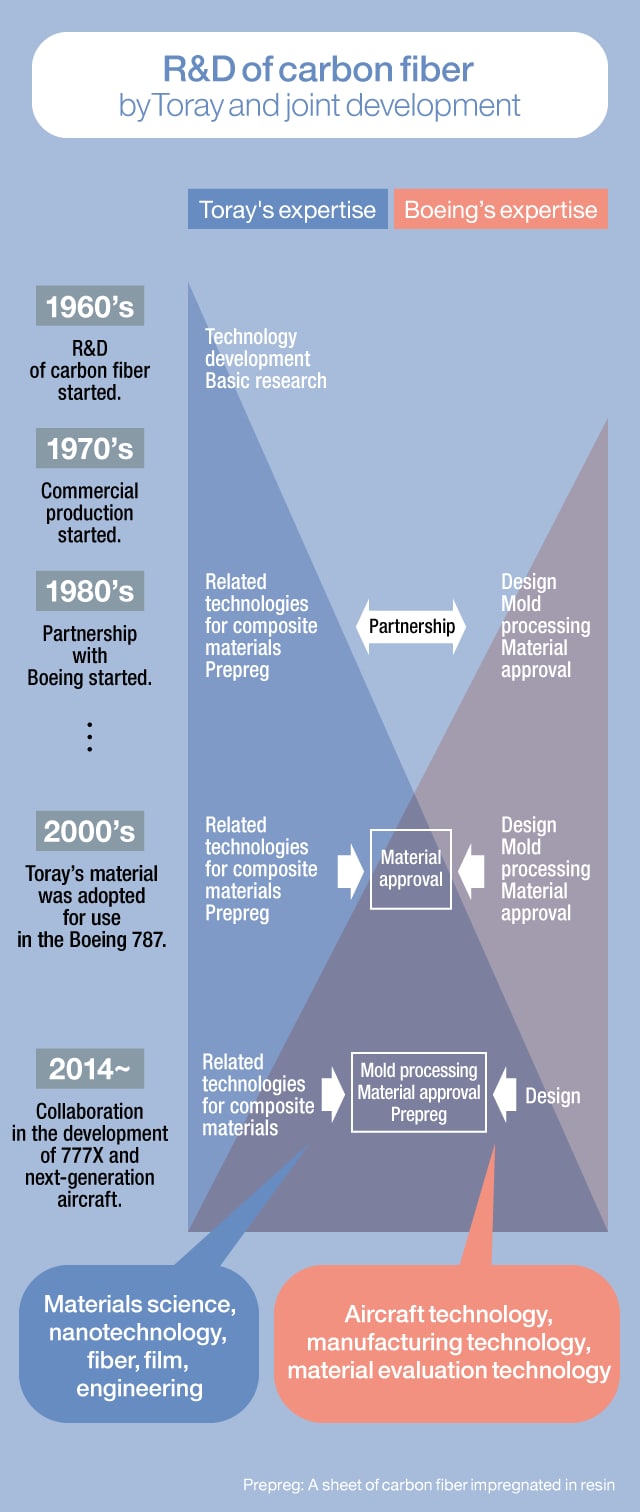

Abe: It takes an enormous amount of time to start up materials research and development (R&D) from scratch and bring it to market. I’ll give you one famous example. Toray started research on carbon fiber in 1961. Commercial production began ten years later in 1971, and it was not until the 2000s that the material was adopted for use in the Boeing 787 airframe.

We started investing in R&D for a material with no market at all. After more than half a century, we were finally able to see significant results. That whole time, we had to hold firm in our belief that this technology will contribute something important to society.

There were a lot of airplanes flying in the 1960s. But in the 21st century, more and more people will be flying around the world. That’s why it’s vital that we reduce the weight of the aircraft to improve fuel efficiency.

I think we were able to continue R&D because our senior members had seen that carbon fiber, which is strong, light and does not rust, would be an optimal material. Underlying all of this was Toray's basic R&D philosophy: creating materials that are useful to society.

■ What can we learn by working to the Ultimate limits of technology?

Maru: What concerns me is the idea that R&D on strong, light materials, such as carbon fiber, may have reached its limit. Over the past half a century, researchers have been steadily refining the technology, and it feels like we've already reached the limit. It seems to me that it will be difficult to make any kind of a breakthrough that surpasses carbon fiber in the future. That's why we think it's going to be easier to solve problems by combining technologies.

Abe: You’re exactly right. This idea of “technology fusion” is very important for solving problems. We need to combine technologies and "multi-materials" to create end products using the right materials in the right places.

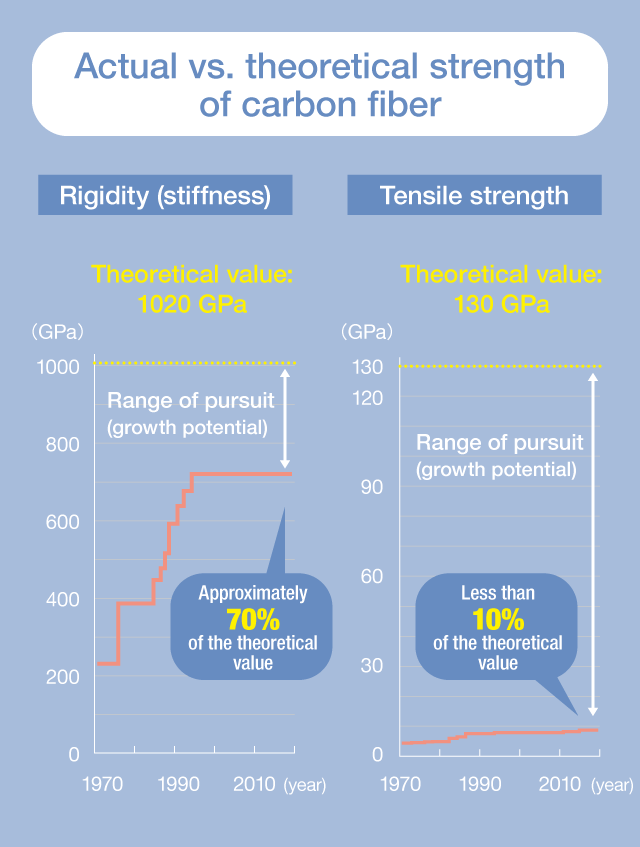

Even so, I believe that that “pursuit of ultimate limits” and “transformational continuity” are the key DNA of Toray's R&D. By taking one technology to the limit, its characteristics can still be improved. Pursuing limits also leads to a kind of innovation, in my opinion. Carbon fiber, for example, is known to be quite strong. In fact, it has only achieved a fraction of its theoretical strength.

Looking at this graph, it’s clear that there’s a wide gap between the theoretical strength and the actual strength of carbon fiber, even though it’s been under R&D for half a century. I hope that young researchers will keep pushing limits and breaking through the barriers that their predecessors were unable to overcome.

Maru: Interesting! After carbon fiber was adopted for the Boeing 787, it seemed to be reaching the limits of its capabilities, but you’re saying there’s still room for improvement? This is fantastic news for us. If there’s a breakthrough in materials, we’ll have more technological parts available to combine.

Abe: That’s right. Speaking of combination, the material used for the Boeing 787 is also a composite material of carbon fiber and resin (plastic). If you think of it like reinforced concrete, carbon fiber is like the reinforcing steel, and the plastic resin is like concrete. The ways we combine the materials affects the strength of the product.

Maru: That makes a lot of sense. That’s a big technical challenge, isn’t it, figuring out exactly how to combine different materials? It’s not easy to combine two very different materials, is it?

Abe: Right, that’s right.

Maru: Do you already have a technology, like a bond, that can bind them together?

Abe: Yes, we do. But it’s still an important technique for us, so we have not applied for many patents.

Many people think that patents serve as technological barriers to entry, but in reality, patents and techniques that are intentionally kept in a black box become barriers to entry only when they are combined. Even if someone came along and tried to reverse-engineer it, there’s no way you could figure out how that adhesive bond in our carbon fiber composites is so strong.

Maru: That’s the wonder of manufacturing, isn't it? Even though Toray is a chemical company, it has built up manufacturing techniques through research and development processes, so no other company can do what Toray does. I really feel like this is one of the strengths of Japanese companies these days.

Abe: We do things in an analog way, not a digital way. You only learn these kinds of spinoff techniques by paying attention to processes and details along the way. Besides, the initial jumping off point, that decision to combine certain technologies, that can only be done by a human being. No matter how much AI advances, I don't think it will be able to solve that problem.

■Will AI increase or decrease the number of genius researchers?

Maru: In the last few years, the AI-based approach to materials development, ‘materials informatics’, has been getting a lot of attention. Up to now, researchers have combined materials through trial and error to create new materials. Introducing AI and robotics streamlines the whole process of hypothesis testing and database creation. Is that something Toray is grappling with right now?

Abe: That's our focus. AI can’t give you the initial input, but I see a lot of potential in the screening part after that.

Maru: I’m personally wondering whether there will even be genius researchers in the future, once AI-based research really gets under way. Flesh-and-blood researchers were holed up in their labs, excited that tomorrow might be the day they might make some great discovery. They examined the results of the experiments incredibly closely, which led to unexpected discoveries.

As you said earlier, I think that “spinoff discovery” is the essence of scientific innovation. I wonder if letting machines handle the research process will increase or decrease innovation. Where do you come down on this?

Abe: We should put the efficiency of machines to good use for screening, things like that. But I personally believe human beings are essential to the process. Human researchers aren’t going anywhere. As someone who has been in R&D for a long, long time, it’s clear to me that the initial idea is discontinuous, you can’t explain it logically. AI is not good at that first spark. The use of AI will not change the nature of researchers, and I’m sure we’ll still have geniuses who make great inventions.

Maru: Thinking about my own specialty, biotechnology, genetic analysis by machines has allowed people to think one step ahead. Until recently, it took a lot of time and manual experimentation to read a gene sequence. But if we can cut that time down, we can spend more time interpreting the data, connecting it to the next idea.

If you can formulate a problem, robotics and AI will get you some solutions, but machines can’t dig deeper into the issue and get to the bottom of it.

The future of R&D is going to change drastically. To me, the human touch is most important in finding those deep issues and setting priorities, so I shifted myself to the "issue finding" side of things.

With all that in mind, I'm curious where the next genius is going to come from.

■Issues are connected on a global scale.

Abe: I couldn’t agree more. When choosing a research theme, Toray places the utmost importance on how it can contribute to society.

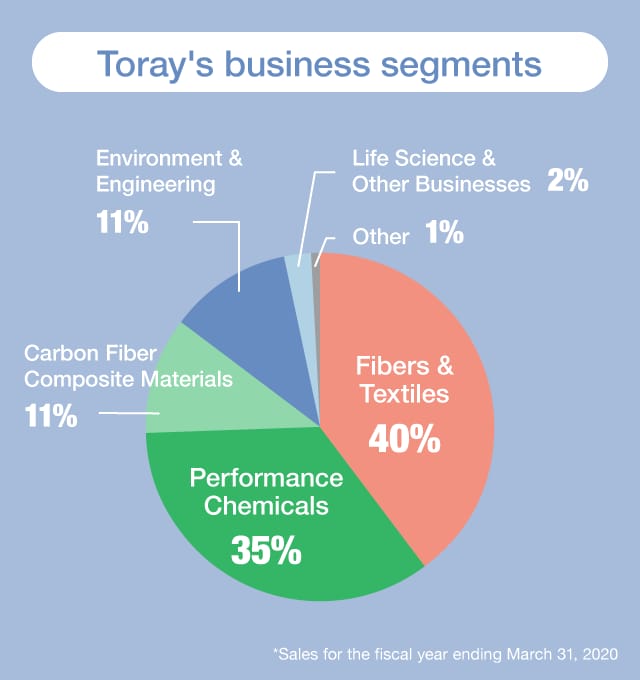

Toray invests about 70 billion yen a year in R&D. But Toray is involved in such a wide range of fields, so analysts always ask me, "How can you cover so many fields with 70 billion yen?” (laughs)

But Toray's R&D is focused on advanced materials. It may seem like Toray is very diversified because of the wide range of business fields we cover, but we are very focused on materials.

When you look back on it, the invention of synthetic polymers gave birth to the synthetic fiber industry, and all the unique products that are now the backbone of the company. Very much like how the invention of semiconductor led to the electronics industry we know today. Materials are hidden in the final product, they aren’t obvious. Sales are small, but history has proven that they are the foundation for the next generation of industries and social systems.

Maru: I totally agree. I’m focusing right now on air pollution as a global issue, and Toray has technologies and products that can be crucial to solving it.

When I went to Delhi, India, I immediately felt a pain in the back of my nose. I thought it was because of the exhaust from factories and cars, but actually the main cause was the smoke emitted from burning straw stubble after a harvest. These kinds of problems are found all over the world. Right now I’m working with a venture company in Singapore on a project named “Creating an air conditioning system for the Earth.”

There are many companies that make air conditioning for rooms. My big question is, who is going to air condition the planet?

Abe: “Air condition the planet?” What’s your approach? I’m curious.

Maru: In a nutshell, our approach is similar to the way the mucus in the nose captures dirty particles. If we can use algae to absorb the heavy metals contained in the mucus, we can address problems with heavy metals and air pollution with one system. I want to try to create a sustainable eco-cycle this way, combining the wisdom of both biotechnology and chemistry.

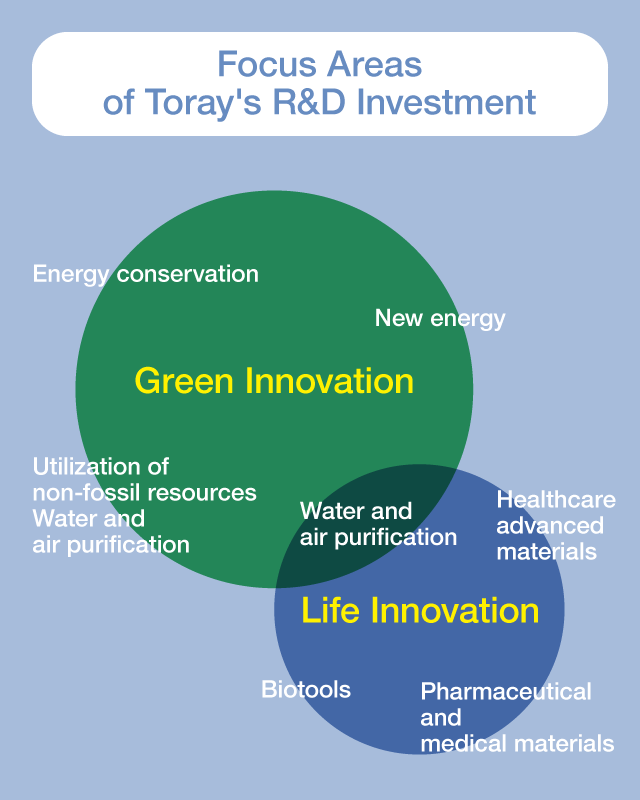

Abe: That’s very interesting. We’re also investing 50% of our R&D investment in green innovation and 30% in life innovation.

The roots of global environmental problems can be traced back to energy, food, water and air. Your decision to focus on air pollution is a natural choice.

Maru: Besides, green innovation and life innovation are connected in the end, aren't they? The cleaner water and air become, the healthier we become. We can solve a lot of health care problems at the same time.

■If researchers are excited about their research, it will continue.

Maru: Today's talk has been very enlightening. At Leave a Nest, we take the position that combining existing technologies can solve problems. But to do that, we need basic research that advances humanity’s base of knowledge. Of course, it’s expensive, and we have to continue our research with no practical application in sight, but without it, when a big issue comes up, we may be missing a really important piece.

Abe: I always tell people that Toray is like a group of venture companies.

Ventures need to find a means of making a living through basic research. Even if the company grows, if we neglect that foundation, the company will no longer be Toray.

To preserve this corporate culture, we encourage “curiosity-driven research” in our company. Researchers are allowed to spend 20% of their work hours on research that doesn’t need to be reported to their supervisors. More precisely, researchers are not just “allowed” but “encouraged” to do independent research. In fact, some of the inventions that support Toray's business foundation today have come out of this kind of curiosity-driven basic research that our people have been working on steadily on the side.

Maru: In short, the world will be created by people who are able to pursue their passions in research, setting their own agenda.

Leave a Nest is working with Toray on an event for elementary school students called the "Blue Sky Science Classroom.” It was started with the aim of encouraging students to use their five senses and feel the fun of science in nature.

People can devote themselves to research with no future in sight because they enjoy it. I think that is what has created the foundation of science and technology.

Abe: I made a comment during an IR meeting a few years ago that got a big laugh. Somebody asked me, "How do you decide what kinds of research Toray will continue on with?” I replied, "If I’m having fun, we’ll keep doing it.”

Maru: (laughs) I really think that’s the essence of science and technology. That’s absolutely right.

Abe: I think it’s true for you, but looking back at my childhood, I think it's important to have the sense of being excited about science. Areas that excite people will attract researchers, increase investment, and progress sustainably as a business.

I would like to not only work on developing new materials, but also keep thinking of ways to convey the fun of science to the world with your help.

Produced by: NewsPicks Brand Design

Edited by: Koji Uno

Written by: Tetsuya Saito

Photographs: Junko Yoda, Kazushige Mori

Design: Kana Tsutsumi