- HOME

- Humanity’s Most Ambitious R&D Project Yet! What Breakthroughs Will Mars Exploration Bring?

Humanity’s Most Ambitious R&D Project Yet! What Breakthroughs Will Mars Exploration Bring?

When it comes to R&D, focusing on the long term is never easy. While many companies try to create products and services that are supposed to change the world, few have the patience and perseverance to keep investing in the basic research required to do so—research which may or may not bear fruit.

As a new era in the space business dawns, what is actually motivating companies to venture into space? To discuss the significance of space development, the most ambitious and longest-running R&D project yet undertaken by humanity, we brought in science writer Kaoru Takeuchi and Kenichi Yoshioka, the General Manager of Toray Industries' Composite Materials Research Laboratories, which engages in R&D into advanced materials.

■Space: The Final Frontier of Knowledge and Technology

──Where does our obsession with going to space come from?

Kaoru Takeuchi: Well, space exploration is the frontier of science, isn't it? I think that we all have, at the core of our humanity, this burning desire to venture into uncharted territory.

Once we had explored every corner of the earth, we began to look beneath the waves, and our curiosity has since brought us into the sky and even beyond the boundaries of our little planet. Space development today is now at the forefront of this curiosity.

There are some people who criticize the amount of resources being poured into space development, saying that it has little to no impact on our daily lives, that budgets should be cut and other areas prioritized instead. But so many of the world’s most advanced technologies are focused on space today. So I might counter that if a country simply stopped funding any space development, it would take it at least a decade to catch back up with other countries in terms of technology.

I should also add that many technologies first developed for space do actually impact general consumers. Telecommunications, radio wave technology, aviation, robotics… Even those radiation shields in microwave ovens. Materials originally developed to withstand the extreme conditions in space are now used here, on Earth. If we want to be considered a country of science and technology, we need to set and pursue ambitious targets in fields like space development. Otherwise, we’ll start falling behind in the world.

Kenichi Yoshioka: I also believe that humanity has only survived for this long because of our innate desire to always reach for the stars. The humans that set out from Africa reached the areas we live in now around 10,000 years ago. We have continued this adventure, exploring the deep seas, high mountains, and have now turned to space. As long as there is a map to be charted, humans will always have that inherent itch to explore.

Our research at Toray is the same. We will continue to do it as long as there is something we can do. We have been doing research on carbon fiber, which is used in aircraft and rockets, for about 50 years now. People are often amazed at how long we have continued with it, but the truth is that the research itself is always evolving.

──In what way does research evolve?

Yoshioka: Well, what often happens is that when I talk about our research on carbon fiber composites with others in the company, I get unexpected questions and advice from experts in completely unrelated fields: pharmaceuticals, polymer processing, or films. If an idea for a new approach comes from these conversations, I just want to try it out immediately.

From the outside, it may look like we’re constantly working on the same thing, but we’re actually changing our approach all the time. In fact, I’d say that for something to be able to serve as a subject for long-term research, it has to allow for changes in approach.

Takeuchi: In science, it’s often pure coincidence that takes research in unexpected directions and leads to new discoveries.

I recently translated a book called "What is Life?" by the British geneticist Paul Nurse. The research that ultimately won him a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was also the fruit of coincidence.

As he describes it, one day he threw a Petri dish of fungus he was experimenting with in the trash and went home. He later felt a sudden pang of regret and jumped on his bicycle, dashed back up the hill to the lab, and retrieved the yeast cells from the trash. This decision to return to the lab led to the discovery of the gene that controls the progression of the cell cycle, which ultimately won him the Nobel Prize.

Image: iStock/Scharvik

Yoshioka: Yes, that kind of thing happens all the time. A failed experiment leads to a breakthrough, or a client from a different industry suggests an approach that actually turns out to work really well.

Takeuchi: It does seem like the fundamentals are the same for both academic and corporate researchers. Both are rooted in human curiosity, the inherent desire to know more and create new things. I guess that research into something that’s interesting is going to be easier to continue with over the long term.

Yoshioka: As a company, we obviously need to consider the potential impact on business, but I agree that there’s certainly a fundamental desire to learn more about something that interests you. It does help to drive research forward.

On the other hand, take carbon fiber for example. Carbon fiber is light, strong, and resistant to deformation. We knew 50 years ago that this material would eventually be used in aircraft. If an aircraft’s frame were lighter but had the same strength, it would improve fuel efficiency. We knew that carbon fiber could help with that, so we were convinced there would be demand for it. That’s why we decided to keep researching it.

I have to say though, despite the company’s confidence in the material’s potential, I don’t think researchers had space development in mind when our research into carbon fiber first began.

■From Fishing Rods to Satellite Antennas

Takeuchi: Space exploration and development requires a wide range of advanced technologies. What are the applications for Toray's carbon fiber right now in space?

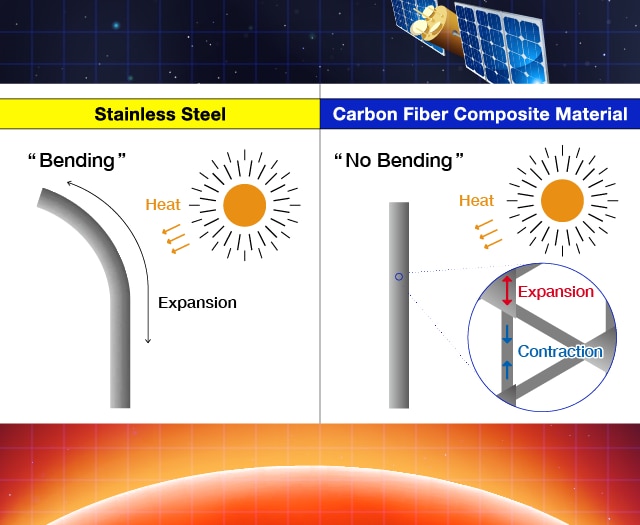

Yoshioka: Our carbon fiber materials are used in the fuselage of rockets and shuttles, as well as in the reflectors of artificial satellite antennas and solar panels. Certain carbon fiber composites have a very low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), which basically means that their dimensions do not change even when the temperature does. This makes them suitable for use in space.

Image: iStock/PragasitLalao

──Could you explain that a bit further?

Yoshioka: In space, there’s a temperature difference of about 200 degrees Celsius between places exposed to sunlight and those in the shade. If a satellite antenna is made out of metal, the surface that is exposed to sunlight will expand and bend.

Takeuchi: I see. Most substances expand when exposed to high temperatures, right?

Yoshioka: That’s correct. But one type of carbon fiber that Toray was developing for use in fishing rods, interestingly enough, actually had a negative CTE.

In order to make a fishing rod that is long but does not snap, you need to increase its stiffness —resistance to deformation when force is applied. The more you control the crystal structure of carbon, the closer it gets to graphite, which rapidly reduces its CTE.

Takeuchi: I see. Then that means that we can create materials that actually contract as the temperature gets higher. And if these materials are used in the right way, we can make antennas that don’t experience deformation because of temperature differences in space.

Note: This image is a simplified depiction of the phenomenon.

Very interesting. I suppose you could call this a byproduct of coincidence, couldn’t you? Since you were originally researching materials for fishing rods.

Yoshioka: Definitely. By trying to develop a material that would be extremely hard but also have high elasticity, we ended up creating a material that contracts at high temperatures—which turns out to be perfect for use in space.

Takeuchi: Humanity has only physically gone as far as the Moon. The International Space Station is only 400 kilometers above the ground, which is about the distance from Tokyo to Kobe!

Considering the vastness of space, we’ve barely scratched the surface. We’ve really only just started on this journey.

■The Ecology of Spacecraft

──There’s a big difference between manned and unmanned space development, isn’t there?

Takeuchi: During my time as a member of a JAXA management committee, I once commented that I would love to see Japan send people to Mars one day, if it became possible.

Of course, I’m aware that this is no easy task, and that unmanned missions such as Hayabusa2 have accomplished remarkable feats. But the impact and sense of achievement you get from an actual person going into space is, I believe, immeasurable.

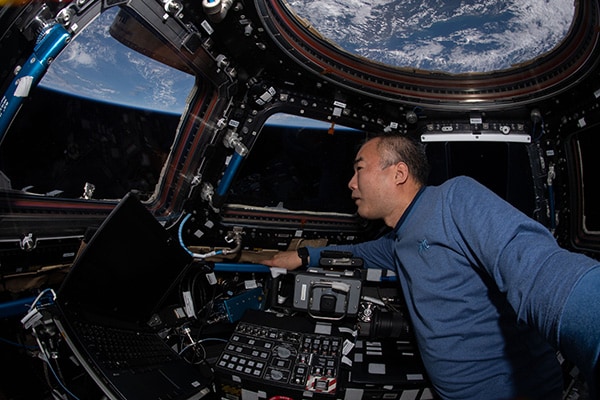

Japanese Astronaut Soichi Noguchi spent around six months on the International Space Station (ISS) in 2021.

Image: JAXA/NASA

Yoshioka: If we want to truly satisfy humanity’s inherent urge to keep moving, it has to be manned missions, as you say.

But going out into the vastness of space means that people must be sealed into a closed environment for very long periods of time. Only a limited amount supplies can be brought on board from Earth, and there’s obviously no way to replenish them out in space.

If we’re going to make progress in space exploration, we’ll need to create an extremely sustainable on-board environment—one that’s safe, comfortable, and compact, of course.

I remember several years ago, there was a joint R&D project between JAXA and Toray to develop a deodorizing fiber called “Mushon®.” Before that, according to astronaut Naoko Yamazaki at least, when moving from the Space Shuttle into the International Space Station (ISS), you were greeted with a distinct smell that resembled a sweaty locker room.

Mushon® is a textile fabric developed by Toray that quickly deodorizes the ammonia odor resulting from sweat and urine. This is achieved by modifying the polymer used as a material for synthetic fibers at the molecular level.

Video: Toray (Japanese only)

──I always imagined space to be odorless, but I guess you can’t exactly put your clothes in a washing machine up there, can you?

Unfortunately not, no. It costs thousands of dollars just to transport a single liter of water. JAXA asked us if we could do something about the smell, and so we applied nanotechnology to develop a long-lasting deodorizing material that reduces the ammonia smell thread-by-thread. Small steps like that will gradually create a more comfortable living environment inside spacecraft.

I think it will also be key to develop technologies that allow water to be fully reused, and also make fuel cells smaller and more efficient.

Takeuchi: A spacecraft is a fully enclosed, confined space. I mean, the only thing that comes in from the outside is solar energy, right? I think the only people who can live in that kind of an environment are people who have some understanding of science and trust in it.

──Do you mean that it’s a matter of scientific literacy?

Takeuchi: Yes. If you’re going to drink your own recycled urine, for example, you will need to have a clear picture of the molecular structure in your head and be confident that it’s scientifically safe to do so. You need that to overcome your natural urge not to drink it.

Image: iStock/ppengcreative

Yoshioka: That’s very true. I remember back when I was at the University of Washington, there was a student who invented a shower that could recycle a small amount of water. From a technological standpoint, the shower she created was perfectly usable. It was how it was perceived that became the issue.

How would people feel about showering in water that others had used before them? In the end, the psychological hurdle proved too much to overcome. I’m sure similar problems will arise on spacecraft, on the Moon, even on Mars.

If we take a look at the wider ecosystem, though, humans are constantly circulating water and air. We also consume crops and animals that grow from the nutrients contained in feces and urine, all without a moment’s hesitation. When you think about it that way, a little perspective could go a long way in overcoming these kinds of barriers.

■Space: The Greatest Outdoors

Takeuchi: That’s interesting. If you look at outdoor activities, people who do serious mountain climbing or camping have no problem filtering water and drinking it. Carrying a lot of water is heavy, so when they run out, they just filter water from a river.

People with a taste for the outdoors get a real sense of being alive when they are out in a natural environment, so they don’t even hesitate or let their emotions get in the way.

Image: iStock/AscentXmedia

This is actually a very scientific attitude to have. People who love the outdoors, those who experience living for a period of time with limited supplies—they have more of a scientific spirit than those who never leave the comfort of the city. In that sense, I think outer space could be considered “the greatest outdoors”.

Yoshioka: At Toray, we have a group of volunteers called the “Space Working Group”, who basically discuss the kinds of materials that will be needed for future space development. Your idea of space being “the greatest outdoors” is very thought-provoking. I would really love to discuss it with the group.

Toray also specializes in water purifiers like Torayvino™ and water treatment membrane technology used to desalinate seawater. If we continue to develop these technologies, you never know—maybe one day they will also be used for space development and outdoor products.

In addition to home water filters, Toray offers water treatment equipment used in seawater desalination and industrial wastewater recycling.

Image: Toray Industries

Takeuchi: What about space suits? One of my hobbies is riding sports bikes, and those sweat-absorbing, quick-drying cycling clothes are honestly amazing. They instantly dry out, and they also help with endurance and maintaining strength.

You mentioned earlier about fibers that suppress odors. Given that exercise is crucial to maintaining physical health in space, I get the sense that many of the materials developed with athletes in mind could also be useful in space.

Yoshioka: It remains to be seen. But I do think that we need to discuss these topics so we can change the very concept of what clothing is.

The clothes we wear today have been optimized to protect us from the heat and cold on planet Earth. But if you do away with this pre-existing concept of “normal” clothing and focus simply on functionality, a whole range of new possibilities opens up. Could film be used? What about painting thermal protective clothing over your body?

Ultimately, it all comes down to perception. Do we really need what we have been conditioned to think that we need? By thinking about what we would take with us into space and how comfortable we would be there, we are, in a way, identifying what our most basic needs really are.

I think that ideas for the next generation of outdoor wear and the clothing of the future will come from brainstorming about these kinds of things.

■Innovation X from Mars

Takeuchi: Can I ask you a question about building different kinds of structures in space?

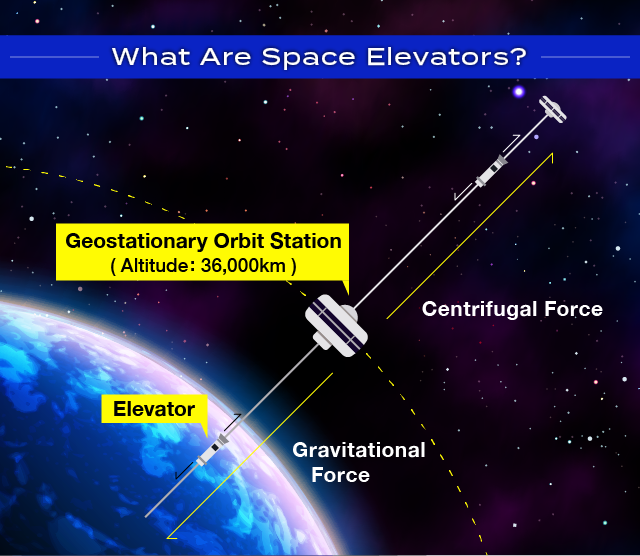

The other day, I was talking about space elevators with Naoko Yamazaki, the astronaut. When you think about the cost of transportation to geostationary orbit, wouldn’t it be much cheaper to build a giant elevator than to keep launching rockets?

We were talking in particular about the potential use of carbon nanotubes.

A space elevator is a proposed planet-to-space transportation system that would be constructed by extending cables from a planet’s surface up to a geostationary orbit.

Yoshioka: They’d be very difficult to construct on the Earth’s surface due to issues with gravity and strength, plus we’d to take measures to prevent accidents with airplanes and other things. But they’re theoretically possible. In terms of specific strength (a material's strength divided by its density; the higher this value, the lighter and stronger the material), carbon nanotubes would be the most suitable of all materials that exist on earth, yes.

Takeuchi: Naoko Yamazaki also doesn’t think we can realistically build space elevators on Earth. Interestingly enough though, she did say that Mars could be where they are first used.

Yoshioka: Oh, that’s interesting. It's true that the Earth’s gravity would likely break the entire structure down the middle, but it could be feasible with the gravity of the Moon or Mars. As for materials, we can either join many carbon nanotubes together to form a long nanotube, or create a carbon fiber with a structure closer to that of a carbon nanotube…

It would be great to sit down and do some proper calculations on this. Who knows, it could lead to a breakthrough for the space elevator, which has always been seen as rather unrealistic.

Image: iStock/narvikk

These kinds of ideas are so important. When you have a group of experts together, one problem is that everyone tends to think that they have already thought of everything. It can be very hard to come up with new ideas. If you can't build it on Earth, why not build it on the Moon? These are the bold ideas that are crucial to driving things forward.

Takeuchi: The members of Toray’s Space Working Group are all experts in different fields, having discussions like the one we’re having today.

Of course, the ideas that come out of these discussions may seem bizarre and unrealisitc in individual fields of expertise. But you can’t reach a real breakthrough unless scientists choose to step out of their comfort zone.

Yoshioka: I completely agree. Breakthroughs are not something that can be calculated. What’s important is to create an environment where they’re most likely to occur and sustain it for as long as possible.

Maybe it’s talking with someone from a different field, like we’re doing today, or maybe it’s thinking about what it would be like to actually set foot the moon or Mars. Or, as you mentioned, questioning whether something is really necessary or not. All of these things help us create the new concepts and ideas we need to push forward.

Takeuchi: When it comes to R&D, both scientific and technological, we can’t lose that adventurous spirit and confine ourselves to a particular set of rules.

Reaching out into the great beyond in search of the innovation that could fundamentally alter how we think as humans—what could be more interesting than that?

Today’s discussion has strengthened my belief that it’s this sense of adventure, this inherent desire to step into the unknown that is ultimately behind humanity’s obsession with space.

Produced by NewsPicks Brand Design

Editor: Koji Uno

Composition: Tetsuya Saito

Design: Toshio Oda

Banner Image: JAXA

English Translation: Luke O’Donovan, Victor Makhnutin